|

Franco-Spanish rivalry in southern North America began in 1564, when French Protestants established Fort Caroline near the mouth of Florida's St. Johns River after the failure of a similar colonization effort at Port Royal two years earlier. This foreign presence so near Spain's rich and vulnerable New World trade routes alarmed King Philip II of Spain, who granted Pedro Menéndez de Aviléz a contract to found a colony and eliminate the French presence in La Florida. In a flurry of activity in September 1565, Menéndez and his expeditionary force founded the settlement of St. Augustine, massacred the inhabitants of Fort Caroline, and slaughtered all but a few members of a shipwrecked French relief force commanded by Jean Ribault near the inlet whose name memorializes this event to the present day: Matanzas, the "place of slaughter". Numerous attempts to dislodge the Spanish from their foothold in eastern Florida would follow, but none would be successful. Meanwhile, Menéndez and his contemporaries nurtured a spectacular but short-lived colonization effort along the Atlantic seaboard through the establishment of an ultimately ill-fated array of missions and outposts that extended from central Florida to the shores of Chesapeake Bay, including the establishment in 1566 and subsequent abandonment twenty years later of a new capital at Santa Elena on today's Parris Island, South Carolina. |

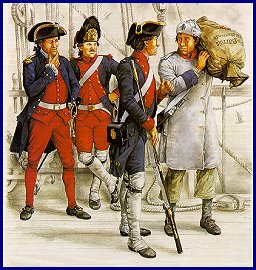

| Above: Eugéne Leliépver, Cadet and sergeant of the French colonial Compagnies franches de la Marine, ca. 1750-1755, cover illustration for René Chartrand, The French Soldier in North America, Parks Canada Historical Arms Series No. 18, (Bloomfield, Ontario, Canada: Museum Restoration Service, 1984) |

Virtually ignored since the dismal failure of Tristán de Luna's 1559-1561 colonization effort at Pensacola Bay, the Gulf of Mexico attracted renewed attention over a century later by both France and Spain after the discovery of the mouth of the Mississippi River by French explorers René Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, and Henri de Tonti, in 1682. The French had been ambitiously extending their presence and influence in North America's interior since the founding of Québec in 1608 by Samuel de Champlain, exploring and establishing outposts along the St. Lawrence River through the Great Lakes and then down the Mississippi River and its tributaries. Control of this mighty river (named the Río de Espíritu Santo by the Spanish), as well as of the other major waterways of North America's interior to which the Mississippi might theoretically be connected, would enable the French to control the subcontinent.

The Spanish had established, in ca. 1679, a small wooden outpost at or near the present community of St. Marks, Florida—Fort San Marcos de Apalachee—to provide protection for their missions in the vicinity. This frail presence was not capable of providing a reliable deterrent to a concerted French colonization effort in the region, and though La Salle's attempt to locate the Mississippi's mouth by sea in 1684-1685 had resulted in failure and his own death, a race for domination of the Gulf Coast and access to its strategically vital harbors and waterways had begun.

Spain immediately began to launch a number of exploratory journeys into the area. In 1686, Juan Jordán de Reina's expedition rediscovered Pensacola Bay as he searched in vain for La Salle's colony, which had passed the Mississippi and landed in Texas before it dissolved into frustration, desperation, mutiny, murder and desertion. In the following year, Andrés Matías de Pez explored Mobile Bay. Finding that to be unpromising as a site for settlement or maritime traffic, Pez concluded that Pensacola Bay was immensely preferable as a site for potential occupation. The most favorable and influential recommendation for the Spanish occupation of Pensacola Bay was made by the respected Mexican cosmologist, mathematician, and scholar Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora following his survey of the area in 1693.

In spite of these glowing recommendations, Spanish authorities vacillated for several years until circumstances dictated the immediate necessity of establishing a colony in the region. Early in 1698, word arrived in Spain that France's ambitious sovereign, Louis XIV, was about to dispatch a small fleet to occupy Pensacola Bay. A flurry of activity followed, and in within days of each other in October 1698 a Spanish expedition from Mexico commanded by newly appointed governor Andrés de Arriola y Guzmán and a French squadron bound from Brest under the authority of Pierre le Moyne, Sieur d'Iberville made full speed for Pensacola.

Arriola's expedition arrived in November to find Captain Juan Jordán de Reina already on site in the process of establishing a foothold at Pensacola, which was named Santa María de Gálve. Immediately, a stockade, named Fort San Carlos de Austria, was established on the Red Cliffs overlooking Pensacola Bay at a site located within what is now Pensacola's Naval Air Station. Spain's newest colonists were a motley lot of hastily conscripted soldiers, convicts, beggars and Mexican half castes who did little to instill feelings of pride or confidence in their officers. Iberville's French squadron arrived on January 26, 1699, only to find the Spanish already occupying—albeit tenuously—the land he had planned to colonize. After a brief and tense exchange of formalities, Iberville withdrew and soon established France's first settlement in the region at Old Biloxi, which would ultimately become the community of Ocean Springs, Mississippi.

The first years were particularly trying for the Spanish colonists of Santa María de Gálve, who experienced alternating periods of destitution and desperation punctuated by fires, Indian hostility, and a stockade that seemed to be constantly deteriorating and eroding down the bluff upon which it was situated. Their often acute lack of essential supplies necessitated their seeking and receiving frequent assistance from the French, with whom an illicit but understandable trade relationship developed. To be sure, the Spanish colonists, who were supplied primarily from Vera Cruz and, to a lesser extent, from Havana, offered trade goods and specie to the French when such were available. For the most part, however, the French assumed the role of benefactor to their Spanish neighbors to the extent that the French often viewed Spain's poor colony at Pensacola as a dependency in fact if not in name.

Spain's relationship with France was greatly strengthened soon after the founding of Pensacola and Biloxi. The frail and impotent Carlos (Charles) II, last of the Hapsburg Spanish monarchs, died in 1700 after having bequeathed the Spanish throne to Philip d'Anjou, grandson of French "Sun-King" Louis XIV. While the new Bourbon monarch, proclaimed as Felipe/Philip V when he assumed the throne of Spain in November of that year, would invigorate and reform many of Spain's antiquated and inefficient institutions, his accession also touched off a violent conflict which found France and its allies and dependencies at war with England, the Netherlands, Prussia, Austria, most of the states of Germany, and, later, Portugal. This conflict, which began in 1701 as a struggle to prevent France from laying claim to Spain, was called the War of the Spanish Succession in Europe and Queen Anne's War when it spread to the American colonies.

It was during this period that the English Carolinians and their Yamassee Indian allies invaded Florida in 1702 and again in 1704. While the invaders failed to capture St. Augustine's Castillo de San Marcos, they succeeded in destroying the city of St. Augustine and wreaking havoc in Apalachee, whose fort was razed, missions were destroyed, and Apalachee Indian population nearly wiped out. The English also sponsored an attack against Pensacola in 1707. The village of Santa María de Galve was destroyed, but the Spanish, with aid and reinforcements from the French, were able to successfully defend Fort San Carlos de Austria and save the colony.

The French colonists remained very active during this period. In 1702, Iberville, assisted by his younger brother and eventual successor, Jean Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, moved the French settlement from Old Biloxi to the first site of Mobile on Twenty-Seven Mile Bluff above Mobile Bay. This site, named Fort Louis de la Louisiane, was the first capital of what would ultimately become the vast province of French Louisiana.

It was from this position that Franco-Spanish colonial relations and trade intensified, but the site of this new settlement proved to be severely vulnerable to flooding and disease while being too far removed from their lifeline of supply at Port Dauphin, established in 1702 on Massacre Island (now Dauphin Island, Alabama). In 1704, a yellow fever epidemic claimed the life of Henri de Tonti, who had been indispensable in his role as a colonial stalwart, explorer, and negotiator with the area's Native American environs. In 1706, Iberville died as well, leaving Bienville in sole authority at the settlement. After English freebooters raided, looted, and burned Port Dauphine in 1710 and Old Mobile underwent catastrophic flooding the following year, Bienville moved the colony to the present site of Mobile and there established a second Fort Louis while rebuilding and reinforcing Port Dauphine in 1711.

In 1717, Bienville began the construction of a new and impressive masonry fortification in Mobile named Fort Condé. At the same time, the French established Fort Toulouse among the Alabamas, southernmost group of the Upper Creek Indians, near the junction of the Coosa and Tallapoosa rivers near modern Wetumpka, Alabama. This secured for the French a strategically vital military, religious, and commercial presence among the Indians and a post from which countermeasures against English colonial trade efforts and territorial encroachments could be launched. French hegemony over the region was further reinforced by Bienville's founding of Nouvelle Orleans—New Orleans—on the east bank of the Mississippi River near its mouth in 1718. Four years later, New Orleans replaced Mobile as the capital of French Louisiana.

Spain's colony at Pensacola, meanwhile, remained weak and impoverished. While the French were occasionally forced to rely upon trade and cooperation with their Spanish counterparts, it is likely that the Pensacola settlement would have failed without aid and support from French Mobile. This was a fact that did not escape Bienville and his associates.

In 1718, another conflict—the War of the Quadruple Alliance—erupted in Europe. This short-lived contest, in which Spain found itself pitted against France, England, Austria, and the Netherlands, afforded Bienville the opportunity, or so he thought, to extend French dominance over the Gulf Coast and westward into Spanish Texas. His desire to expand France's (and his own) influence eastward on the Gulf of Mexico had already been demonstrated a year earlier; in 1717, while forts Condé and Toulouse were being built, the French covertly established a small military post named Fort Crevecoeur on the eastern shore of Florida's St. Joseph's Bay between Pensacola and the then-abandoned Spanish settlement at St. Marks. Carefully placed just beyond view from the water, the work was nonetheless discovered by a Spanish patrol. Before the Spaniards could return in force, Fort Crevecoeur was abandoned early in 1718. Soon thereafter, realizing the necessity of and responding to Indian requests for the maintenance of a presence in the region, the Spanish began construction of a new and stronger Fort San Marcos de Apalache at St. Marks.

When news arrived that France and Spain were at war, Bienville had no need to conceal his ambitions for French expansion at Spain's expense. In 1719, the French seized Santa María de Gálve, the Spanish recaptured the settlement and were foiled in an abortive attempt to invade Louisiana, and the French returned to overpower and occupy the colony and the bay it guarded.

Meanwhile, a small contingent of French troops from Fort Jean Baptiste at Natchitoches raided the nearby Spanish mission of San Miguel de Linares de Los Adaes. While this inglorious effort succeeded in ending the site's role as a mission, the triumphant French soldiers returned from Los Adaes with only a handful of chickens they had "captured" as the terrified padres and their charges ran frantically away. In 1721, Los Adaes was reoccupied as a presidio. Eight years later, Los Adaes became the official capital of the new Spanish province of Texas, a role it would maintain until it was abandoned in 1773 after having been replaced by a newly named capital at San Antonio.

When the war in Europe ended in 1720, Philip V demanded, and Louis XV conceded, the return of Pensacola Bay as a Spanish possession. After having burned the village of Santa María de Galve and Fort San Carlos de Austria to the ground, the French withdrew from and returned the charred remains of the first Pensacola settlement to Spanish control in 1722.

This was the only time that the French and Spanish colonies would engage in armed conflict in North America. For forty years following this isolated and ultimately inconsequential series of events, the French colonists at Mobile and their Bourbon Spanish neighbors enjoyed a relatively cordial, if somewhat one-sided, relationship.

The Spanish, meanwhile, removed their colony to Punta Sigüenza on Santa Rosa Island in 1723, where they remained through the trials of "storms and high tides" until a hurricane demolished Santa Rosa Punta de Sigüenza in 1752. In 1757, the Viceroy of New Spain—under whose authority the colony had existed since its founding—ordered the entire colony to do what many of the settlers had already begun to do: relocate for a third and final time to the mainland, at and around the small, fortified mission of San Miguel in what is now Pensacola's historic district. Later that year, a royal order established the name of the settlement as Presidio San Miguel de Panzacola. The inclusion of "Panzacola" in this place name lended official recognition to the familiar name by which the area and its bay had been known for a century. Thus the original native Panzacola population, whose name in Choctaw means "long haired people" and who had reportedly been exterminated by the Mobila Indians years earlier, was memorialized in history.

Soon after the establishment of Pensacola at its present site, Spain's hegemony over Florida was interrupted and France's colonial tenure in North America was forever terminated as a consequence of Britain's overwhelming victory in the 1754-1763 French and Indian War, called the Seven Years' War (1756-1763) in Europe. Though the Gulf Coast region was spared from experiencing the violent and sanguinary events that characterized this struggle in northeastern America and Europe, the consequences of this conflict were imosed with frightful clarity upon the region's French and Spanish environs.

By 1762, France's defeat by Britain and its allies was virtually assured. In spite of this, Spain joined its Bourbon neighbor in an offensive-defensive alliance in February of that year. Within months of its ill-advised coalition with France, Spain lost its vitally important possessions of Havana and Manila to the British. As 1762 neared its close, France ceded Louisiana to its woe-stricken Spanish ally in the Treaty of Fontainebleu. By the terms of the 1763 Treaty of Paris, which ended the conflict with a decisive British victory, France surrendered all its claims in North America; Spain's claim to Louisiana and the city of New Orleans was confirmed; and Britain took possession of Florida while agreeing to return Manila and Havana to Spain.

Later that year, British forces occupied a greatly enlarged Florida, which now extended from the Mississippi and Iberville rivers to the Atlantic seaboard. The terriory was so large that it was split into western and eastern provinces divided at the Apalachicola River, with the capital of West Florida at Pensacola and that of British East Florida at St. Augustine.

Spain was slower and far less decisive in taking possession of what would now be called Luisiana. After a weak and irresolute 1766-1768 Spanish attempt to establish authority in that province ended with the expulsion of governor Antonio de Ulloa y de la Torre Guiral during an uprising by local inhabitants, Ulloa's replacement, Alejandro O'Reilly, returned in August 1769 with a large military force of Spanish troops and firmly asserted Spain's supremacy over Louisiana. Soon thereafter, the last French troops and officials left the province. France's colonial empire in North America had come to an end.

A French presence in the Gulf Coast region was very briefly renewed during the American War for Independence. In 1779, Spain once again allied with France in its ongoing war against Britain. Upon hearing of this, Spanish Luisiana's young and energetic governor Bernardo de Gálvez Madrid Cabrera Ramirez y Márquez, who had already been providing covert but crucial support to American rebels operating in the rebellion's western theatre of operations, immediately made plans and began to consolidate the necessary resources to reconquer British West Florida for Spain. In September 1779, Gálvez's forces seized Manchac, Baton Rouge, and Natchez. In March 1780, the governor captured Mobile after a brief siege. Finally, in March 1781, after being delayed by storms and other logistic difficulties, Gálvez invested Pensacola.

|

The siege of Pensacola was a combined Franco-Spanish military effort in which a total of over 7,000 Spanish and French soldiers and sailors were arrayed against a greatly outnumbered British, Hessian, Loyalist, and allied Creek Indian garrison of slightly less than 2,000 men. The French contributed approximately 750 soldiers from the colonial Du Cap infantry regiment; the Agenois, Gatinois, Cambrésis, and Poitou regiments of regular line infantry; and detached members of French royal marines, engineers, artillery, and other supporting branches of service to be actively engaged in the siege itself. Additionally, hundreds of French sailors and shipboard garrisons of French infantry under naval authority stood in reserve and on the eight French warships that participated in the campaign. |

|

| Above, Left: Sergeant of Chasseurs, Agenois Regiment; Above, Right: Officer, Gatinois Regiment. From John Mollo and Malcolm McGregor, Uniforms of the American Revolution (New York: MacMillan Pub. Co., 1975), plates 206-207. | ||

On 8 May 1781, a shell fired from Gálvez's siege lines ignited the magazine of the Queen's Redoubt at the head of Pensacola's British defenses. The resulting explosion killed many of the redoubt's defenders and sealed the West Florida capital's fate; two days later, the British garrison surrendered. Shortly thereafter, Spain's French allies withdrew from Florida. While their active service in Florida was now at a close, many of the same French troops who served at Pensacola would return to participate in the Franco-American siege of and victory at Yorktown, Virginia in October 1781. With this final and decisive victory over its ancient British foes, Bourbon France punctuated the closure of its presence in North America with a definitive statement.

![]()

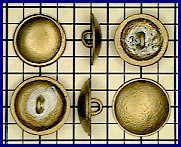

FRENCH COLONIAL MARINE BUTTONS, Ca. 1700-1763

The Compagnies franches de la Marine, comprised of infantry under royal naval authority, formed the backbone of France's colonial military establishment in North America. While other French regular and colonial units served in the New World, no other forces served continuously or over such a vast territorial expanse. The classic button pattern worn by these troops from Canada to the Gulf of Mexico until the end of the French colonial period was a convex, rimmed, cast brass type exemplified by the specimens shown above. Until the 1730s, these buttons were made with integrally cast, slab-like shanks with drilled eyes similar to those in use by the Spanish military establishment at the time (upper left/Dauphine Island, Alabama). By the 1740s, the drilled eye form had been replaced by a similar form featuring a cast brass rimmed button body with an inverse staple-like copper or brass wire eye soldered or brazed to the button's back (upper right/Mobile, Alabama and Lake Champlain, New York).

![]()

France began to mandate and utilize unit-specific marked buttons for its soldiers in 1762. While process began too late for these buttons to see use in North America before the end of the French colonial period in 1763, it set a precedent for European military fashion that, in turn, was emulated by Britain in 1768. The regulation and design of marked buttons for the various components and ranks of the French armed forces progressed rapidly through time until a plethora of different button designs evolved to identify and distinguish every regular and auxiliary constituent element of that nation's military establishment.

Between 1762 and 1780, the French military establishment was reorganized six times. Each of these reorganizations resulted in the formation of new regiments, the dissolution or renaming of old ones, and the merging of others into consolidated units bearing either new or old names. Through all these and later changes, however, one thing remained constant. Each French infantry regiment was assigned a name and a corresponding regimental number, and that number was placed on the buttons of the men in the regiment to which that designation had been assigned. As a matter of standard practice but with a few exceptions, these infantry buttons bore their appropriate regimental numbers in their centers. On each button, this number was encircled by a foliole, or foliated broken line, with a dot in the center between the disconnected ends of that line. The entirety of this design was inset from the outer edge of the button. Other button and insignia designs were created for and assigned to the other regular and auxiliary elements of the French military establishment.

Students, collectors, and collections administrators dealing with French military uniform buttons of this period should remain cognizant of several considerations related to French military buttons and uniform goods in general:

The uniforms for each regiment were normally rotated every two years on a staggered basis. Therefore, it was not standard practice for an entire regiment receive its entire complement of replacement uniform goods at the same time, and a soldier who transferred into one regiment from another would still have worn his old uniform until it was replaced through fresh regimental issue or attrition. Normally, each regiment's colonel would order uniforms for his men. The cost of these uniforms would be deducted from the soldiers' pay. This both allowed the regimental commander to make a profit and insured that the unit's supply of uniform goods would be monitored and maintained.

If a regiment received new uniforms soon or immediately following a change of regulations for that unit and new uniform regulations were issued a year or two later, there would have been a period following the issue of those newer regulations during which at least some the troops in each regiment would still have been wearing their older uniforms (and buttons) until all the soldiers in the regiment received new, regulation issue clothing during the course of the regular two-year replacement cycle.

"White metal" and "yellow metal" button colors in the French military establishment did not necessarily imply, respectively, pewter and brass buttons for enlisted personnel as was the norm in the British, Spanish, and American armed forces. French "White metal" enlisted issue uniform buttons were usually made of a conventional or "lighter than usual" brass or bronze alloy coated with an inexpensive but attractive mixture of tin and mercury to impart a silver-like, or "white", appearance. This coating almost invariably quickly erodes away when the artifact upon which it is applied is interred in the ground, leaving the button or other, similarly treated metallic object to be subsequently recovered bearing little or no trace of its having ever been thus coated or plated.

French enlisted personnel most commonly wore one-piece, solid cast (and occasionally subsequently die-stamped) buttons with durable, "turret"-like, integrally cast, tapered rectanguloid and double perforated shanks. This shank configuration was unique to French manufacture and use, and it was retained in service through and beyond the Napoleonic period.

French military officers' buttons were of the same construction as those worn by officers of their European and American counterparts. These buttons were of stamped gilt or silver (or silver plated) foil which was crimped around perforated bone or wood backs. Crossing catgut cords were threaded through the backs' perforations to provide for their attachment to the uniforms upon which they were to be affixed. These "bone-backed" buttons were infamously unpopular with the officers who wore them, and soon after the American War for Independence they were phased out of service by Britain, Spain, and the United States. However, France continued to use these buttons until the end of the Napoleonic period.

Over 750 French ground forces were directly engaged in the Franco-Spanish siege of Pensacola, while hundreds of other French soldiers and sailors were held in reserve or in service on nearby ships during that campaign. Serving in the siege lines and trenches with Bernardo de Gálvez's Spanish regular and veteran provincial forces were members of the 16th (Agenois), 18th (Gatinois), 20th (Cambrésis), and 26th (Poitou) regular regiments of infantry; the colonial Du Cap regiment of infantry from St. Domingue (modern Haiti); Royal Artillery; Royal Naval Infantry and Artillery; and probably some French engineers and staff officers. Nearby were members of the 52d (La Sarre) and 83d (Angoumois) regiments as shipboard infantry garrisons under naval authority as well as members of the French Royal Navy.

As previously mentioned, many of the same French forces that served at Pensacola also participated weeks later in Washington's and Rochambeau's joint Franco-American operations at Yorktown, Virginia in the autumn of 1781. Some French military button examples from military camps in the Yorktown vicinity have been included here for illustration purposes when examples of those units' buttons from the siege of Pensacola have not been available for inclusion in this section.

|

AGENOIS REGIMENT, 1776 REGULATION ISSUE The Agenois Infantry Regiment was created by a splitting of the 8th (Bearn) Regiment in 1775. With the reorganization of 1776, the Agenois Regiment was assigned the number 14 and authorized to wear "white metal" buttons. In 1779, the Agenois Regiment was renumbered the 16th and "white metal" buttons were again prescribed for the unit. In the 1779 reorganization, the number 14 was assigned to the Forèz Infantry Regiment, whose buttons were to be of "yellow" metal. At this time, an example of a 16th regiment button for this unit is not available for illustration. Members of the Agenois Regiment served at the siege of Savannah in 1779, Pensacola and Yorktown in 1781, and the capture of St. Kitts in 1782. |

GATINOIS REGIMENT, 1776 AND 1779 PATTERN The Gatinois Regiment was assigned as the 18th regiment in 1776 and again in 1779, although in 1776 the unit was to wear "yellow" buttons and in 1779 the color of buttons and trim was changed to "white". This brass example could have been used in either case, as in the French military estalishment most "white metal" buttons were in fact brass or bronze buttons plated with a coating of a tin and mercury amalgam-like alloy. This regiment was present at the siege of Savannah in 1779, and later at both Pensacola and Yorktown in 1781. |

|

|

CAMBRÉSIS REGIMENT, 1776 AND 1779 REGULATIONS Like the Gatinois Regiment above, the Cambrésis Infantry Regiment retained the same regimental number (20) but the colors of its buttons and trim were reversed. In 1776, the unit was assigned white/silver buttons and trim, and in the 1779 regulations the color was changed to yellow/gold. Like the 18th button shown above, this example, recovered from Pensacola's historic district, could have been either color before it was lost and buried in the ground. The Cambrésis Regiment served at the 1779 capture of Grenada and St. Vincent, as well as during the siege of Savannah, in addition to service at Pensacola in 1781. |

POITOU REGIMENTAL BUTTONS Another unit that retained its regimental number but changed its trim colors in the 1776 and 1779 regulartions was the 26th (Poitou) Regiment of Infantry. In 1776, the regimental button and trim color was yellow/gold; in 1779, the color was altered to white/silver. In addition to service at Pensacola, the Poitou Regiment was also present at the unsuccessful Franco-American siege of Savannah in September-October 1779 and as ship's garrison troops in the naval battles off Martinique in April and May 1780. |

|

|

Above left to right: French naval officer, 1778-1783; Bombardier, Bombardiers de la Marine, 1778-1783; Fusilier, Corps royal de l'infanterie de la Marine, 1778-1783; and Fusilier, Barrois Regiment (not involved in Franco-Spanish operations), 1776-1782. Source: René Chartrand and Francis Back, The French Army in the American War of Independence (see bibliographic citation below), p. 32, plate H. |

NAVAL

AND COLONIAL ARMIES A variety of buttons like those above were worn by enlisted members of the French Armées Naval et Coloniale (Naval and Colonial Armies), which included naval, marine, and colonial infantry forces. Naval and Marine forces wore gold or "yellow" colored buttons, while colonial troops were called upon to use "white" or silver colored versions of these patterns. Officers wore foil-clad, bone backed versions of these and other, similar "anchor button" designs. Such buttons would have been worn by the French naval and marine forces, as well as by the colonial Du Cap regiment, during the 1781 siege of Pensacola. |

ROYAL CORPS OF ARTILLERY, 1776-1790 This is one of three very similiar button varieties issued to the rank and file of the French Corps Royale de L' Artillerie during the 1776-1790 period. During this period, this branch of France's army wore buttons like those of most regular line infantry regiments but bearing the number "64". In 1786, the Royal Corps of Artillery of the Colonies began to receive a distinctive button whose device included an upright anchor between the numbers "6" and "4". |

|

|

FRENCH BUTTONS • PENSACOLA These buttons, recovered from Pensacola's historic district, were intended for issue to the 40th (Ile de France) and 44th (Royal-Vaisseaux) infantry regiments. These regiments are not listed as having seen service during the siege of Pensacola. It is postulated that they were either worn by newly transferred replacements from these regiments or, more likely, by members of these units serving as shipboard infantry garrisons on the French warships involved in the siege. |

|

Bibliography of Selected Sources

Appleyard, John, Pensacola: The Spanish-French Confrontation 1660-1720 (Pensacola, Florida: John Appleyard Agency, Inc., 1993

Avery, George, 1996 Annual Report for the Los Adaes Station Archaeology Program, Management Unit 1 (Natchitoches: Department of Social Sciences, Northwestern State University of Louisiana, 1996)

Bowden, Jesse Earle, Gordon Norman Simons, and Sandra L. Johnson, Pensacola: Florida's First Place City, A Pictorial History (Norfolk, Virginia: The Donning Company, 1989)

Chartrand, René, The French Soldier in Colonial America (Historical Arms Series, No. 18, Bloomfield, Ontario, Canada: Museum Restoration Service, 1984)

Chartrand, René, and Francis Back, The French Army in the American War of Independence (Osprey Men-at-Arms Series, No. 244, London: Osprey Publishing Ltd, 1991)

Coker, William S., and Hazel P. Coker, The Siege of Pensacola 1781 In Maps (Vol. VIII Spanish Borderlands Series, Pensacola: The Perdido Bay Press, 1981)

Dupuy, R. Ernest and Trevor n. Dupuy, The Harper Encyclopedia of Military History (Fourth Edition) (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1993)

Fallou, Louis, Le Bouton uniforme français (Seine, France: La Giberne, 1915)

Gannon, Michael, Ed., The New History of Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1996)

Hamilton, Peter J., Colonial Mobile (Southern Historical Publications Number 20, Reprinted from the Revised [1910] Edition, University, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press, 1975)

Higginbotham, Jay, Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane 1702-1711 (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1977)

Holmes, Jack D.L., A Guide to Spanish Louisiana 1762-1806 (Louisiana Collection Series, Birmingham, Alabama: Dr. Jack D. L. Holmes, 1970)

Hurley, Marian L., A Collector's Guide to French Military buttons of the American Revolution 1775-1783 (Suffern, New York: Marian Hurley, 1998)

Lefferts, Lt. Charles M., Uniforms of the American, British, French, and German Armies in the War of the American Revolution 1775-1783 (Reprinted copy of the 1926 edition, Old Greenwich, Connecticut: WE Inc.)

Leonard, Irving A., "Pensacola's First Spanish Period (1698-1763) Inception, Founding, and Troubled Existence", in James R. McGovern, Ed., Colonial Pensacola (The Pensacola Series Commemorating the American Revolution Bicentennial, Volume I, Hattiesburg, Mississippi: University of Southern Mississippi Press, 1972), pp. 7-54

Mollo, John, and Malcolm McGregor, Uniforms of the American Revolution (New York: MacMillan Pub. Co., Inc., 1975)

Parks, Virginia, Pensacola: Spaniards to Space-Age (Pensacola: Pensacola Historical Society, 1986)

Parks, Virginia, Ed., Siege! Spain and Britain: Battle of Pensacola March 9-May 8, 1781 (Pensacola: Pensacola Historical Society, 1981)

Rea, Robert R., "Pensacola Under the British (1763-1781)", in McGovern, Ed., Colonial Pensacola, (op. cit.), pp. 57-88

Rogers, William Warren, et al., Alabama The History of a Deep South State (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1994)

Rush, N. Orwin, Spain's Final Triumph Over Great Britain in the Gulf of Mexico: The Battle of Pensacola March 9 to May 8, 1781 (Florida State University Studies Number Forty-Eight, Tallahassee: The Florida State University, 1966)

Starr, J. Barton, Tories Dons & Rebels, The American Revolution in British West Florida (Gainesville: The University Presses of Florida, 1976)

Thomas, Daniel H., Fort Toulouse, The French Outpost at the Alabamas on the Coosa (Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press, 1989)

Weber, David J., The Spanish Frontier in North America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992)

Weddle, Robert S., The French Thorn: Rival Explorers in the Spanish Sea 1682-1762 (College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press, 1991)

Wright, J. Leitch, Florida in the American Revolution (Gainesville: The University Presses of Florida, 1975)

Acknowledgments:

René Chartrand; R. Wayne Childers; Pensacola Historic Preservation Board; and Arthur C.,

Imogene, and Samuel A. Standard

Special thanks are extended to Mr. and Mrs. Ed and Marian Hurley for their invaluable information, assistance, and advice.